Although the coasts of New Caledonia have always been the scene of countless shipwrecks, that is unknown shipwrecks brought to the attention of ArkéoTopia, another way for archaeology by one of its members which led to the refloating of the Aventure in terms of research. The first official excavation of the Corvette in 1975 by ship’s lieutenant, Patrick Banuls, and the documents which came from it, led ArkéoTopia to collaborate with Fortunes de Mer Calédonniennes (Nouméa) on a new excavation of the wreck in July 2018. Before the results and the reports of the excavation comparing the 1975 and 2018 operations are published, we will go through a little bit of history: on one hand, the journey of Eugène du Bouzet, captain of the Aventure at the time of the shipwreck in 1855 and that of the French Navy corvette, against the backdrop of the geo-political context of the time, and on the other hand, the adventure of the first mission in 1975.

|

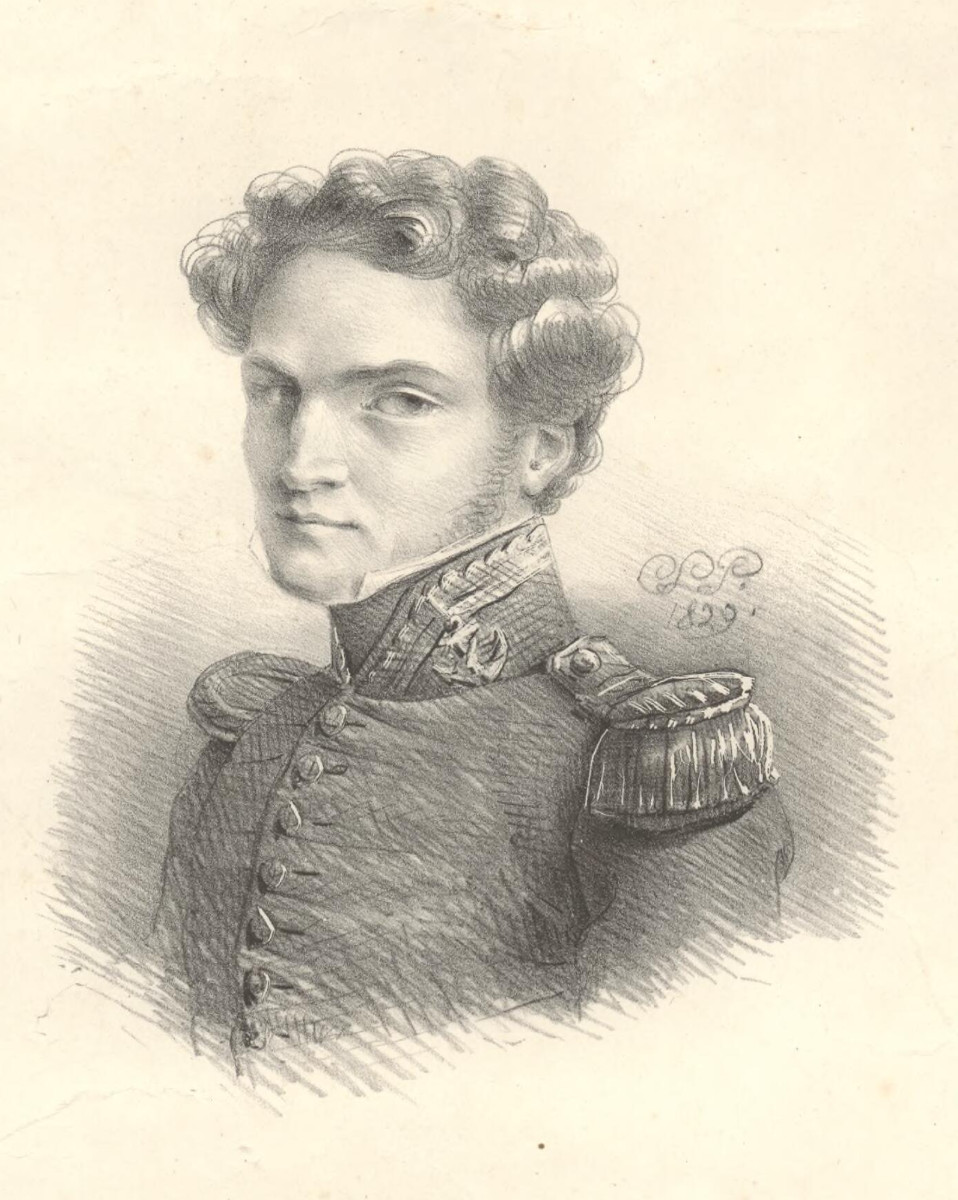

| Fig. 1. Portrait of Joseph Fidèle Eugène du Bouzet © C.L.P. 1829. National Librairy of Australia. obj-136044403. |

A captain of merit

Despite its short life of barely more than one year, the Aventure made its mark on History because, on this journey from Brest to Port-de-France (Nouméa) in 1854, the ship’s captain was Marquis Joseph Fidèle Eugène du Bouzet, first Commander of the New Caledonia.

Du Bouzet was born in Paris on December 19, 1805 and joined the Navy in 1818. He became a ship’s lieutenant in 1831 at the age of 26 and was given his first command in 1834 at the age of 29. Two key moments in his young career were his participation in the journeys of circumnavigation with Bougainville (1824-1826) and acting as second in command on the Zélée during Dumont d’Urville’s expedition to the South Pole (1837-1840)..

Interested in science, mankind and the world in general, he studied ancient languages and had a great general knowledge. His behaviour, his work, his taste for observation merit numerous compliments. Discreet and modest he, however, also showed himself to be firm as a commander, a quality appreciated by his superiors and which made him a sought-after officer.

Rear Admiral Legoarant de Tromelin, commander of the naval station of Oceania, said of him:

As modest as he is skilled, Mr du Bouzet, in the reports he has sent to me from different ports of call, always tries to highlight the merit of his officers without thinking of taking most of the credit for himself. Endowed with a perfect sense of organisation, and with uncommon precision and timeliness, this officer has the most powerful credentials for promotion. He has a well-founded reputation as a good sailor, and the entire Navy has great esteem for him, esteem for which he is worthy in every way.”

Anonyme, Sept. 1867, p. 697

His service record is just as remarkable. In 1842, during his stay of one month in Papeete, he managed to negotiate a permanent agreement between the catholic missionaries headed by Father Caret and Queen Pomaré. Five years later, lieutenant commander, and captain of the Brillante, he arrived in Balade and Pouébo in New Caledonia to rescue the Marist missionaries threatened with massacre by the Kanaks.

In March 1854, he was appointed Governor of the French Institutions in Oceania and Commanding Officer of the Naval subdivision in OCEANIA (Tahiti, Marquises, New Caledonia), and his story and that of the Aventure will always be linked to that of New Caledonia.

The Aventure left Brest on June 10, 1854 with the new governor on board. Thanks to the medical report of the chief doctor aboard, Dr Lucien Pénard (Pénard, 1854-1855), we know the situation on board. Designed to transport on average 240 men, it reported 415 people on board, 252 crew and 163 passengers. The presence on board of passengers is explained by the fact that, in those days, ships were a form of long-distance public transport. Even if the Aventure was taking a company of naval infantry and an artillery detachment to control the new colony, numerous people were just simple travellers. There were even three women and a child on board.

Dr Pénard also pointed out, on noticing 45 service exemptions during the 161 day journey from Brest to Tahiti, that “To summarise, considering the extreme overcrowding on the Corvette and the difficulty of maintaining good hygiene during the crossing from Brest to Tahiti, the medical results have been incredible and have greatly surpassed my expectations on departure”. After a month in port in Tahiti, the Aventure headed for New Caledonia.

|

| Fig. 2. View of the harbour of Port-de-France in Nouméa in 1857. Louis Le Breton – Le Monde illustré 2 p. 4 Domaine public via Wikimedia Commons |

At the time Imperial France was at war with England in a race for the colonies. On one hand, trade in sandalwood was forming contacts between Europeans and Kanaks. On the other hand, missionaries were settling in New Caledonia. The insecurity experienced by the latter incited them to call on their respective powers, the United Kingdom for the protestants and Napoleon III’s France for the Marists, to bring order to the territory. Lastly, at this time, France was looking for a place with a milder climate than the awful one in Cayenne to set up a penal colony, while the British colonies of Australia were extending their colonial reach to ensure complete anglophone dominion over the Pacific islands.

So, the two countries were just waiting for the triggering factor that could justify taking possession.

The massacre at Yenghebane (1) gave Napoleon III an excuse. He gave instructions to several French war ships to seize New Caledonia, on condition that it had not already been annexed by the English. The first to arrive was Admiral Febvrier Despointes who took control of Grande Terre in Balade and proclaimed it a French colony on September 24, 1853.

On June 25, 1854, the French military founded Port-de-France as the capital of the colony, a simple garrison which rapidly became a small town.

It is in this context that the Aventure and du Bouzet entered Port-de-France on January 18, 1855 and that the latter proclaimed the land to be the property of the French State on January 20, 1855 (Bulletin Officiel de la Nouvelle-Calédonie 1853-1855, Act n°18, p. 26).

The Aventure was the home of the transitional Governor, governorship later being left in the hands of commander Testard. For three months he set about preparing a detailed report on the Island’s resources, the possibility of developing agricultural land, the best areas to set up in and the construction of the first administrative buildings in the territory. He devoted himself to completing the fortifications and accommodation for the garrison and the civil servants in Port-de-France. He put his companions to work, each in their area of expertise such as Jean-Jacques Anatole Bouquet de la Grye (27 years old), hydrographer and astronomer in charge of mapping the land and the lagoons or like captain de Génie Lucien Florent Paul Coffyn to whom we owe the grid plan structure of the future capital of the colony. He also established a general political framework and a strategy for concessions and maintained relations with the indigenous people to balance the parties involved. He also studied the exploitation of mineral resources.

After his study of the Grande Terre and having handed over the reins to Commander Testar, Mr du Bouzet set off for Tahiti on the Aventure on April 16, 1855 in the company of the dispatch boat the Duroc.

Interrupted by the sinking of the corvette recounted hereafter, his return journey finally took place on July 1, 1855 when he left Port-de-France for Tahiti and new assignments.

The Pacific, Algeria, and Brazil took him to the end of his career of Rear Admiral. He requested retirement on the grounds of ill-health. He was made Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour. Three years later, on September 22, 1867, he succumbed to his illness. He is buried in Brest.

|

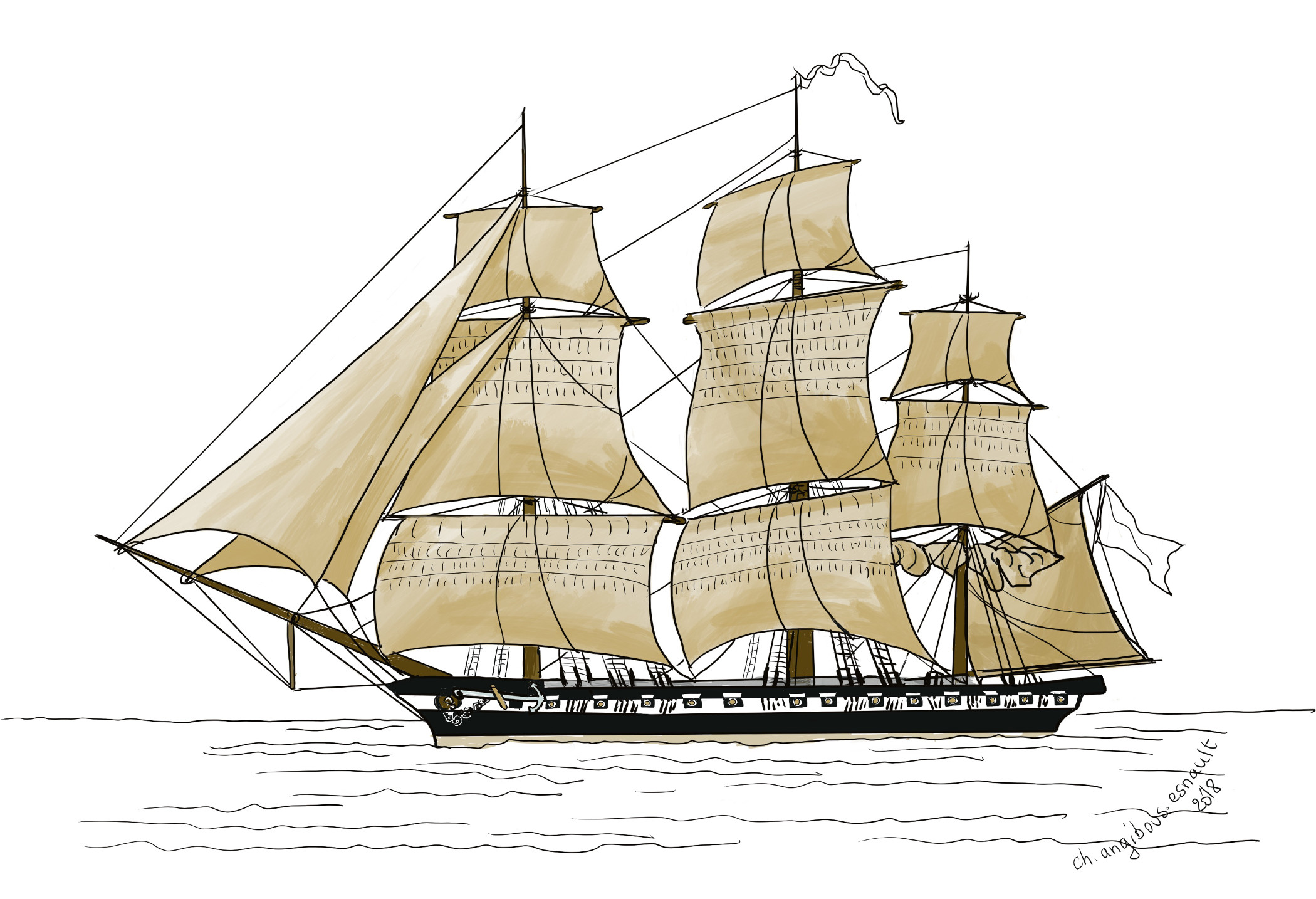

| Fig. 3. The Aventure from a painting on the Favorite sistership. © Christiane Angibous-Esnault, 2018. |

The Aventure sinks

Technical specifications

Category: warship

Construction class: “Aventure”

Type: corvette

Hull: wood

Tonnage : 1,193 tonneaux

Dimensions: 43m x 12m x 4.92m

Sails: 1,490 m2

Weaponry: 22 canons

Characteristics: Sylvestre Plan; XXIII

Numbers: 229 – 250 men

Construction site: Brest dockyard

Chronology: keel laid May 2, 1849, launched November 27, 1852, commissioned March 11, 1854, struck off April 28, 1855 (sank)

What the archives recount

On April 16, 1855, during his return journey to Tahiti, Du Bouzet wants to inspect the Ile des Pins (to the south east), Britannia (Maré – Iles Loyauté) and Balade (on the north east coast of the Grande Terre). There have been high seas for five days. The Ile des Pins is reached, and four days are spent there, but three days later, nobody disembarks in Britannia. The violence of the wind makes them give up looking for anchorage. Giving the assignment of going to Balade to the Duroc, Mr du Bouzet decides to turn around and go directly to Tahiti. It is April 27, 1855 at 7 o’clock in the evening.

The direct route seems impossible because of the trade winds. The wind is blowing from east-south-east, very fresh. It is decided to pass the Ile des Pins on a long port side tack southward, between south-south-west and due south. The speed is 6 – 6.5 knots, under low sails, topsails and topgallant sails.

Nonetheless, the commander, fearing that they will not be able to pass by the Ile des Pins whose position in relation to the Britannia is still unsure, decides, to be on the safe side, to take a north-east tack at two o’clock in the morning. He orders the watch officer to wake him up at that time. It is 8 o’clock in the evening. There is clear moonlight, the ship is moving along at 6 – 7 knots. At midnight, the weather is still fine despite a few clouds to the south.

At two o’clock in the morning, the watch officer sends someone to wake up the commander and to tell him that, although the wind has picked up noticeably, it is still manageable, that the sea is good and that the lookout has reported nothing particular around the ship. Remaining moonlight enables them to see quite far despite strange reflections on the sea. The commander sends word to continue on this run and suggests changing tack a little later.

|

| Fig. 4. Medical report by Dr. Penard, 1854-1855 © Rapports médicaux, SHD-Brest Archives – 2F9-32. |

“A disastrous idea!!…. because hardly ten minutes later, the Corvette, doing at least 8 knots, comes face to face with reefs. The lookout shouts from the foremast yardarm: ‘rocks on the port side’, then: ‘rocks to starboard’, then: ‘let it drift’, and by drifting the Aventure ends up perched on the edge of a coral reef.“

Pénard, 1854-1855

The commander, who has suddenly appeared on the bridge, orders the sails to be lowered and furled, which is done but not without some problems. The order is given to cut away the masts, but the corvette, coming around on its bow, comes almost directly into the wind. Du Bouzet hopes for a moment, despite the appearance of the reefs, that the ship is going to pass over them. The tremors continue. The rudder breaks. The corvette leans to port. The ship is lying on its side, with a fathom of water in the rear two thirds of the ship, and with nine fathoms to the front third, the rudder has been swept away.

“After a quarter of an hour, the rear half of the ship up to the gangway is aground, we get ready to launch the lifeboats. I have the port canons thrown overboard to straighten and lighten the ship; the corvette shifts a little to starboard; water then starts to enter the hold so quickly that the hold becomes inaccessible and the brave men who had gone to save the provisions have to be evacuated. Fortunately, the lifeboat tackle had already been brought up.“

Bouzet du, Joseph, Fidèle, Eugène (1855)

The ship breaks up just behind the foremast and ten minutes later it is announced that the ship is filling up and that it is already impossible to get into the officers’ accommodation and none of their personal effects can be saved. So, the crew sets about putting the lifeboats to sea (the moon has set and the night is dark), a manoeuvre which is carried out with skill and precision and is a credit to the bosun and his experienced sailors. (…) Finally, towards six o’clock, daylight comes, and to everyone’s joy it is apparent that they have ended up on the North reef of the Ile de Pins, (…), opposite Houpe cove which is covered in coconut trees full of fruit. The disembarkation starts, first to be sent ashore are the sick, the ship’s apprentices, and the men, who on board would be of secondary use, and who, ashore, could immediately start setting up camp. The topmen and gun crew stay onboard to try and save as many valuable and useful items as possible. (…) And it is then that we ourselves leave the ship, having had, fortunately, no serious injuries to treat. Our two assistants accompanied the sick.

Pénard, 1854-1855

The ship is lost. The rescue is carried out in perfect order. Commander du Bouzet leaves the ship last. He certainly deserved the tributes of his men who shouted, “Long live the Emperor! Long live the Commander!”

On land, the crew settle in under tents put up among the palm trees by the sailors armed with sails and rigging, and the officers settle in under a large pirogue hanger in poor condition which also serves as a galley and general store.

For three days there is a dearth of food, having only been able to save 15kg of biscuits and 2 barrels of eau-de-vie from the ship. The ration at each meal is half a biscuit and a boujaron (2) of eau-de-vie. Fortunately, this is supplemented by coconuts found on-site and a little brackish water from a nearby spring which a few natives, present when they disembarked, had shown them. Then, the next day they are able to get water from an excellent spring, also mentioned by the natives, which is a league from the camp.

As soon as they leave the ship, Mr du Bouzet sends someone to let the mission and chief Vendegou know of their situation. A pirogue is sent by the missionaries in Vao and arrives loaded with provisions. The hunger does not really stop until May 2, with the arrival of the Hydrographe and on the 4th with the Sarcelle.

On May 10, everyone boards the Sarcelle heading for Port-de-France, except 40 men who stay behind to try and recover, the sea permitting, anything salvageable from the wreck and to keep watch over the items saved. A month later, this small group of men return to Port-de-France by their own means.

Finally, on July 26, 1855 the English, three-masted barque Sultana, under the command of captain Tipper, repatriates everyone to France. As for governor du Bouzet, he returns to sea on the Duroc heading for Tahiti the day after the departure of his men.

To conclude this event, we must mention that Mr du Bouzet was tried in Brest in 1856 for the loss of his vessel. Despite what could be seen as a lack of good judgement and without doubt because of his numerous, known virtues, he was acquitted unanimously, and his sword was returned to him by Rear-Admiral Aimable Jehenne, chairman of the war council, with these words: span style=”font-size: 12pt;”>”In a sailor’s life there are setbacks which, in the eyes of superiors and colleagues, only prove to increase the stature of someone like you, who has served them so well” (Anonyme, Sept. 1867, p. 698).

A first official excavation

Whilst the wreck of the Aventure was known to the natives and the history buffs, it had never been surveyed.

In 1975, the ship’s lieutenant Patrick Banuls, commander of the Dunkerquoise patrol boat, is assigned to the wreck of the Aventure. During a transfer of command, he had, in fact, heard out about this ship from a young chief of staff. The latter had served under the command of the lieutenant of the Pouliquen, who was interested in military shipwrecks in New Caledonia and had already discovered the Seine but had not had time to investigate the Aventure. When the Dunkerquoise arrived in Nouméa, Patrick Banuls requested this assignment. So, he discovered the wreck of the Aventure on 7 July 1975.

Due to a lack of resources, the task is not very easy. It is thanks to Paul Kompouaré – from the Ouapa tribe – who shows him the site of the shipwreck according to oral lore, that he is able to locate the site (Banuls, 1975). They only have four days to explore the wreck.

The area is divided into squares by divers at depth and free divers around the reef. As they get too close to the reef, an inflatable dinghy comes to the rescue and is turned over by the rollers, sending two diving tanks into the sea; and it is while recovering this equipment from a depth of 3m that the team discover the first signs of the Aventure, an object shaped like a bridge covered in coral turns out to be cast iron. The area then reveals other items.

Everything that could have been recovered by the du Bouzet team had been recovered, so the wreck does not have much to show, especially as the weather and the sea has moved what was left, and that the large concretion of coral has also done its work. In addition, more than a hundred years after the sinking, the Dunkerquoise was not the first to explore the site, this area having been visited by numerous divers. Nevertheless, a few large items emerge that the team try to dislodge and bring to the surface.

In this way 1 rudder gudgeon, 6 large anchors, 3 canons and various unidentified objects appear.

|

| Fig. 9. The anchor on arrival at the museum before restoration (a) and on display after restoration (b) © Maritime Museum of New Caledonia Inv. MTNC 85 1 22 |

The biggest task is a 4-metre anchor. The commander goes looking for empty, 200-litre barrels that could act as flotation devices to help bring it up. The containers are delivered to the site by police helicopters.

The anchor starts moving, carried by 23 barrels, but the weight, the swell, and the resistance of the barrels break the tow ropes. Since 1855 the currents have spread the remains of the ship in the channel at a depth of between 10 and 20 metres, but this time the anchor descends to 60 metres!

The next day, by replacing the ropes with a metal cable, a second anchor is successfully brought to the service and towed behind the Dunkerquoise.

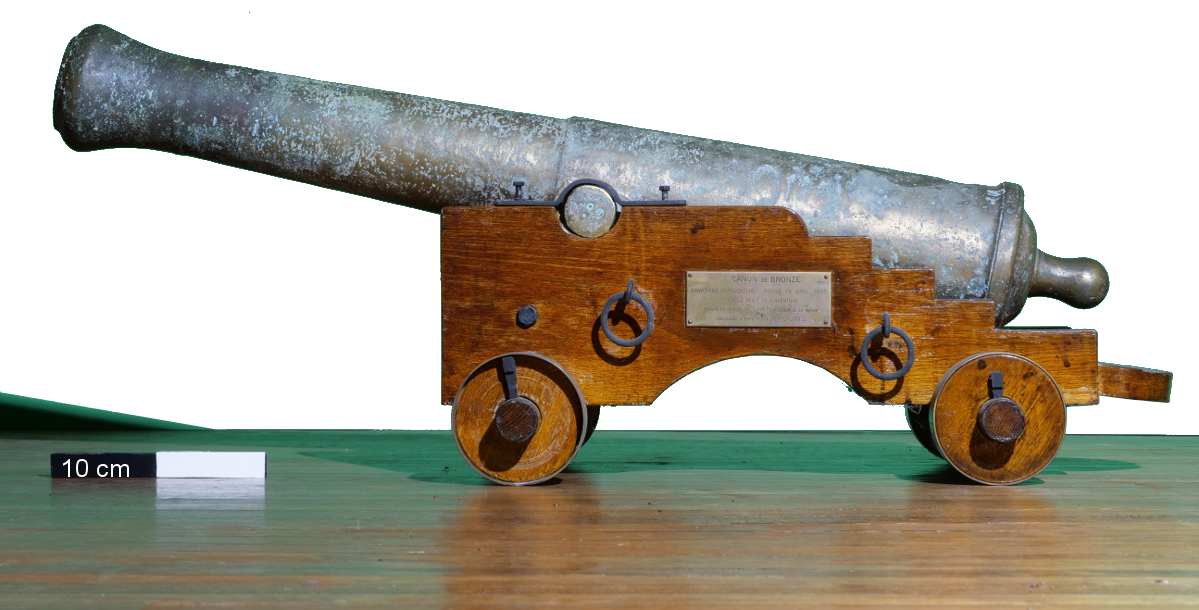

In the meantime, various objects are identified and listed and some are raised to the surface, including a small ‘perrier’ canon that the ship’s captain Claude Verdier, commander of the New Caledonia National Navy, allows to be kept in the wardroom on the Dunkerquoise.

During a ceremony, the other items are handed over to Luc Chevalier (3) by captain Verdier and commander Patrick Banuls, who had carried out the assignment.

This is how a stock anchor, a gudgeon and a pump body became part of the museum collection, while the ‘perrier’ canon remains in the possession of the French Navy.

Since its discovery, the wreck was visited in 2002 and 2016 by Fortunes de Mer Calédoniennes who were able to recover new artefacts. The report is waiting to be published. The next assignment in July 2018 will enable the research to be completed (artefacts, ship structures, weapons etc.) and to compare all the data.

On-going research

Forty years after the first official mission, ArkéoTopia set about finalising the research concerning the Aventure using previously unseen documents provided by Patrick Banuls. This work started in 2014 with a comparative analysis of literature, localisation of recovered remains and discussions with participants of the official mission in 1975.

The Dunkerquoise, having finished its service in January 1987 and the ship having been scuttled, the question remains of where to find the small ‘perrier’ canon kept on board. Was it put somewhere, or has it disappeared?

After several months of investigation, it was found on the naval base of Chaleix in Nouméa. Once its origins were confirmed and authorisation obtained from the Chief of Staff, ArkéoTopia asked its local partner Fortunes de Mer Calédoniennes to take some useful photos (fig. 10 and 11). Cleaned and placed on a gun carriage specially designed for it, it can now be found in the multi-purpose projection room, identifiable via its commemorative plate.

During the research, my attention was drawn to an artefact held by Patrick Banuls. The study of the object, the report from the dig, previously unseen documents, and the plan of the excavation in his possession have enabled us to cross-check the information with the underwater photographs taken by J.-P. Mugnier of Fortunes de Mer Calédoniennes during one of his dives. The operation in July 2018 (cf. infra) should enable us to confirm the current theory about the function of this artefact.

In addition, various documents from the archives are still being studied.

Different theories and points not yet elucidated have opened up new possibilities, and a request to carry out underwater and land exploration in July 2018 has been filed at the South Province and the Ile de pins. This request, put forward by Fortunes de Mer Calédoniennes in partnership with ArkéoTopia, has the aim of finding further information and new elements. The operation should especially allow various cross-checking such as:

1. The plan of the 1975 excavation with the present location of the site and the objects,

2. The place where the 40 crew members, who had to retrieve elements from the wreck, camped out according to the archives, compared with that which can be identified on site.

So, the operation will enable us to complete the identification and inventory of the artifacts that the Aventure could still reveal. The remains brought to the surface will be taken care of by the New Caledonia Maritime Museum. This research will contribute to enhancing the map of shipwrecks in the area and to improve knowledge of the life of sailors at this time.

Sources and bibliography

Anonyme (Sept. 1867) 1 et 2 : « Nécrologie », Revue Maritime et Coloniale 21, p. 695-700.

Anonyme (Sept. 1867) 1 et 2 : « Nécrologie », Revue Maritime et Coloniale 21, p. 695-700. Banuls Patrick (1975) : Compte-rendus et rapport de mission de 1975, archives personnelles en cours d’étude par ArkéoTopia.

Banuls Patrick (1975) : Compte-rendus et rapport de mission de 1975, archives personnelles en cours d’étude par ArkéoTopia. Bouzet du, Joseph, Fidèle, Eugène (1855) : Rapport adressé à l’Établissement français de l’Océanie, Ministère de la Marine, Archives 67.

Bouzet du, Joseph, Fidèle, Eugène (1855) : Rapport adressé à l’Établissement français de l’Océanie, Ministère de la Marine, Archives 67. Brou Bernard (1974) : « Trois notes biographiques », Bulletin de la Société d’Études Historiques 18, p. 45-48.

Brou Bernard (1974) : « Trois notes biographiques », Bulletin de la Société d’Études Historiques 18, p. 45-48. Leblic Isabelle (2003) : « Chronologie de la Nouvelle-Calédonie », Le Journal de la Société des Océanistes 117, p. 299-312.

Leblic Isabelle (2003) : « Chronologie de la Nouvelle-Calédonie », Le Journal de la Société des Océanistes 117, p. 299-312. Macé C. (3 mai 1856) : « Nouvelle-Calédonie, Île des Pins. Naufrage de la corvette l’Aventure », L’Illustration 688/27, p. 279-282.

Macé C. (3 mai 1856) : « Nouvelle-Calédonie, Île des Pins. Naufrage de la corvette l’Aventure », L’Illustration 688/27, p. 279-282. Pénard Lucien (10 juin 1854 – 23 Xbre 1855) 1 / 2 / 3 : Rapport médical, Rapports médicaux, SHD-Brest – Archives – 2F9-32.

Pénard Lucien (10 juin 1854 – 23 Xbre 1855) 1 / 2 / 3 : Rapport médical, Rapports médicaux, SHD-Brest – Archives – 2F9-32. Pisier Georges (1974) : « Notes d’histoire calédonienne. Le naufrage de l’Aventure à l’Île des Pins », Bulletin de la Société d’Études Historiques 18, p. 10-16.

Pisier Georges (1974) : « Notes d’histoire calédonienne. Le naufrage de l’Aventure à l’Île des Pins », Bulletin de la Société d’Études Historiques 18, p. 10-16. Roche Jean-Michel (2005) : Dictionnaire des bâtiments de la Flotte de guerre française, de Colbert à nos jours. Tome 1 (1671-1870), auto-édition.

Roche Jean-Michel (2005) : Dictionnaire des bâtiments de la Flotte de guerre française, de Colbert à nos jours. Tome 1 (1671-1870), auto-édition.

Notes

1. The Alcmène corvette was sent on an exploratory mission by the French government in 1850. The aim was to study the possibility of colonising and setting up a penal colony. The operation ended tragically in the north of la Grande Terre, at Yenghebane. Several officers and crew were massacred and eaten.

2. In the navy, a ‘boujaron’ is a container, most often made of tinplate, used in the galley to distribute liquid rations to the crew. It holds a little less than a sixteenth of a litre. By implication, this was the daily ration of alcohol received by serving sailors in the colonies, or fishermen in certain countries.

3. Luc Chevalier is at that time curator of the Museum of Nouméa which, on the initiative of two underwater archaeological associations, Fortunes de Mer Calédoniennes and Salomon, became the New Caledonia Maritime Museum on October 4, 1999.

Find anecdotes in french about the Mission Aventure venture in the news on the crowdfunding campaign Dartagnans Mission Aventure.

Acknowledgements and many thanks for their help and collaboration

Patrick Banuls (explorer of the Aventure), the naval Base of Chaleix in Nouméa, Alain Braut (Department of Military History in Vincennes), Luc Faucompré (photographer with Fortunes de Mer Calédoniennes), Jean-Olivier Gransard-Desmond (Dr. of Archaeology, ArkeoTopia), Philippe Houdret (President of Fortunes de Mer Calédoniennes), Valérie Vattier (Director of the Maritime Museum of New Caledonia).